A new publication we’ve been reading, Vietmeme, focuses on civic life in Vietnam as seen through and influenced by the web. After interviewing Anh-Minh Do from the Tech in Asia about the Vietnamese internet, I found that Vietmeme founder Patrick Sharbaugh’s work, expertise, and unique position of having a deep understanding of both the internet in the US and Vietnam allowed me an opportunity to delve more deeply into Vietnam’s net. As Sharbaugh told me, in some ways the Vietnamese internet is really hard to gauge as an outsider, partly because of the low use of more open and searchable platforms like Twitter or Weibo. Because of distance and these limitations, it was great that Sharbaugh was able to discuss over email some of the more intricate workings of the internet. I have broken that discussion into three sections which I will publish weekly here. To start out, I wanted to get a feel for Vietmeme and Sharbaugh’s motivations for starting it.

. . . . . . . .

Ben Valentine (BV): What is Vietmeme?

Patrick Sharbaugh (PS): I first started thinking about Vietmeme late last year, when I was invited to organize a panel discussion on Vietnam’s online civic engagement at a conference in Singapore called CeDEM Asia, presented by the Asian Media Information and Communications Centre. I rounded up some colleagues in Vietnam who could join me, and at the conference we discussed ways in which new social media tools appear to play a role in influencing governance and politics in Vietnam. And in researching that and talking about it with some of the people there, I realized that there’s really a very active culture of online civic engagement in Vietnam, though many people outside the country aren’t aware of it.

Vietmeme emerged last March as a shared project with Đăng Nguyễn and Mai Huyền Chi, plus our two research assistants: Ngoc Chi Le and Bao Hung Vu. With it, we want to do a couple of things. One is to feature longer, well-researched articles and posts that discuss news topics that are getting a lot of attention in Vietnamese online communities, and to give some sense of what Vietnamese people are saying about them, along with some necessary background information that puts it all in a context foreign readers can understand a little better. And we also want to be able to highlight some of the vast pool of creative visual memes that are constantly bubbling up out of this churn.

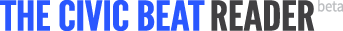

This image alludes to the censorship by communist party officials of a locally produced film earlier this year which caused an online furor. This image, remixed in the style of vintage Vietnamese wartime propaganda posters, reads, “New changing Cho Lon Youth! We’ve changed! How about you, Censorship Committee?”

We do this across a few different platforms. Our website, Vietmeme.net is mainly where we post longer analytical articles. On our Twitter feed, @Vietmeme, we try to feature at least one ‘Vietmeme of the day’ image post each day, and on our Facebook page we have links to all that stuff and hope to be able to nurture and grow a more interactive community based on it all. It’s still very much early days for us; we’ve only been actively posting for a few months, and we’re a small team of just five people, all of whom are working on this in our spare time. I’d love to grow Vietmeme to the point where we’re providing something approaching the level of visibility for the online community here that, say, Tea Leaf Nation does for China, and to have an active community of members on Facebook and Twitter who are regularly feeding us memes and links.

A popular satirical meme that epitomizes the Vietnamese Minister of Health’s many difficulties in 2013: “Let me ask you this: without me, how would funeral services thrive?”

BV: What is one great example of Vietnamese netizens civic engagement online?

PS: One recent example that springs to mind is that of the Minister of Health here in Vietnam, which my colleague Chi Mai wrote about at Vietmeme a few weeks ago.

Last July 20, three newborn infants tragically died just minutes after receiving standard Hepatitis B vaccinations in in Quang Tri Province. The next day the Minister of Health, Nguyen Thi Kim Tien, traveled to Quang Tri — but not to meet the three grieving parents. She was there for a groundbreaking ceremony, and she chose to ignore the easy opportunity to pay the families a visit. On being questioned by reporters, the Minister excused herself by claiming a full schedule, and declined to provide a statement about the children’s deaths, claiming a commission had been assigned to speak to the media on the matter. On July 21, another infant in Binh Thuan province died following yet another Hepatitis B vaccination. Still, the Ministry offered no condolences to the grief-stricken parents and no explanation to the nation for why the infants had died.

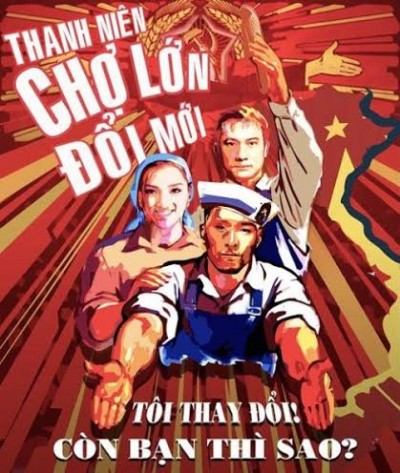

Another image of the Vietnamese Minister of Health from Vietmeme, riffing on the many unflattering observations from netizens on her appearance, as well as on popular calls for her resignation in the wake of multiple scandals in the health sector in 2013: “I use this anti-shame cream everyday on my face and the 502 super glue on my ass, so don’t you dream that I’d resign.”

Vietnam’s Internet exploded with recriminations over the incidents and the Minister’s responses. The outcry ranged across hugely popular discussion forums like the motherhood-related WebTreTho and the technology-focused TinhTe. It swept over countless blogs and videoblogs. It swamped the comments sections of news articles on the topic, prompting advertising-minded editors to order up still more such articles to take advantage of surging page-views. (Although the news media are answerable to the state, they are also profit-seeking businesses owned by the state, which sometimes generates interesting conflicts.)

A Facebook paged dedicated to the resignation of the Minister of Health. “Resign, Minister of Health!”

An anonymous group created one of many Facebook pages devoted to the issue, entitled “Resign, Minister of Health!,” (above) calling for signatures for an online petition. Their stated goal was to reach 15,000 signatures, at which point page administrators said they would forward the petition to the National Assembly. By August the count of membership of the Facebook page had reached 20,774 (it’s now at more than 105,000). Comments on the page, and across many of the online platforms, began to move beyond the still-unresolved issue of the Hepatitis B vaccine and into the many other problems plaguing Vietnam’s health sector because of poor oversight, rampant corruption, inadequate facilities, and substandard training.

But again, one of the most visible and effective forms of speaking out on the topic of the Health Minister and the vaccinations was the tsunami of remixed images that poured across the Vietnamese Web — created using simple, now-ubiquitous software tools and easily shared and re-shared in classic meme fashion via social media. Some were quite sophisticated: images of a faux new national stamp created to honor the Minister of Health for her service, which for some reason wouldn’t stick; thousands of netizens delighted in explaining that’s because people insisted on spitting on the front of the stamp instead of the back. Others were of humbler provenance: photographs of the Minister featuring mock captions, quotations imagined or real, and even hand-illustrated comics, cartoons and repurposed Japanese manga panels.

All of this would be perfectly normal, even expected, in the United States or most any developed democratic society today. But everything about this is unprecedented in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam — the tools, the network, the availability of information, and especially the impulse for citizens to engage so openly and critically. Last month, in the wake of yet another spate of missteps and scandals for the Health Ministry, at least one mainstream media outlet openly called for the Minister’s resignation: something that would have been inconceivable just a few years ago. Apparently it’s the first time in Vietnam’s history that a state-controlled media outlet here has done such a thing. Not surprisingly, the Ministry of Communication had the article taken down almost immediately, but many people captured screengrabs of it and so it’s continued to be shared widely across Vietnam’s internet. It’s an impressive and remarkable illustration of the new power of Vietnam’s online public sphere.

For several years now, international media have made much of Vietnam’s growing community of political bloggers, many of whom are openly critical of the government and its policies and often advocate for political, even democratic, reform. But for all their courage and their good intentions, I think most of those bloggers may be too shrill and openly antagonistic to gain much popular support in such a Confucian-oriented, collectivist culture as Vietnam. On the other hand, 2013 saw an explosion in Vietnamese image-based social sites similar to 9gag and 4chan: sites like hai.VL, Epic.vn, Doremon.che, Ubox, the Tuyết Bitch Collection on Facebook, and many others. The visual memes commentary these sites and their users have generated are significant in Vietnam not because they’re amateurish, or often puerile, or short-lived, though they are all those things. It’s because they are achieving what all the finger-wagging from the bloggers and Western democracies have not: they are changing minds. And they’re achieving this precisely because they are amateurish and ephemeral and, yes, often silly. They’re not shrill. They’re not stern. They may be angry, but it’s an anger leavened by humor and irony.

. . . . . . . .

This is the first of three interviews between Patrick Sharbaugh and I, we will be publishing in the coming weeks.

Patrick Sharbaugh is from South Carolina, USA and spent most of his life working as an editor and journalist for city magazines and alternative newsweeklies. In 2007 he decided to spend a couple of months in a small town in Japan when the housing and stock market crashed in the US, rippling through the international market. Recognizing that it was not a good time to look for a new job, Sharbaugh stayed in Japan, moving to Kyoto and then later to Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, where he was offered a position at an offshore campus of an international university there as their first lecturer of their communications program. He has been teaching communication theory there now for five years, focusing on Asian cyberculture and media’s effects on society.