As a teenage boy from the Midwestern United States, I decided to do a semester abroad in Tanzania because I was looking for an adventure. After spending some time there, I found that the story that had been constructed for me was overly simplified – Tanzania was not Africa; it wasn’t corruption, it wasn’t famine – it wasn’t any one thing. I saw during my travels there, and then later with social media, a more complex image of the historically marginalized region than traditional media has allowed, especially for me as a white and western onlooker.

Diversity in news media, as it is in ecology, is much healthier than the opposite – indeed Tanzanian news has experienced a long drought. One is always hearing of the problems up north in Kenya, or west in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Tanzania is one of the more stable countries in Africa, sadly making it less newsworthy. I am continuously disappointed by the lack of coverage of Tanzania, and increasingly seek to hear from the people who live and are from there through social media.

I went to Tanzania for five months in 2007, I am no expert. I haven’t extensively studied the politics, cultures, and history of the country,and therefore have a very specific and limiting awareness. Despite five months of immersion and KiSwahili classes, I am completely unqualified and uncomfortable speaking for Tanzania and its people. With over 120 ethnic groups and numerous languages and climates, five months was no time at all. My experience there was steeped in contradictions of which I am not prepared or perhaps articulate enough to resolve.

I went to Tanzania for five months in 2007, I am no expert. I haven’t extensively studied the politics, cultures, and history of the country,and therefore have a very specific and limiting awareness. Despite five months of immersion and KiSwahili classes, I am completely unqualified and uncomfortable speaking for Tanzania and its people. With over 120 ethnic groups and numerous languages and climates, five months was no time at all. My experience there was steeped in contradictions of which I am not prepared or perhaps articulate enough to resolve.

One small but perhaps indicative experience for me was during a two week homestay my school arranged in northern Tanzania near Lake Natron. I was staying with a Maasai family which consisted of a man and three wives, many children, and three homes (one for each wife). I slept in a mud and dung hut with several children on a bed made from sticks and cowhide. I spent my days there walking with two of my host father’s sons whom I watched as they herded goats, all in the shadow of Ol Doinyo Lengai, a semi active volcano that was slowly murmuring ash. In many respects, it felt as far from home as possible.

Of the two sons, one was studying to be a wildlife tour driver in Arusha and spoke enough Swahili for us to attempt to communicate; the rest of the village mostly spoke KiMaa, the language spoken by the Maasai people, which I could only greet in. The two carried a spear and a walking stick each, wore traditional brilliant red Maasai clothes, and always had on hand their cheap plastic candy bar cell phones which is their primary access to the internet. Listening to pirated music like Tanzanian hip hop band X Plastaz or Bob Marley on an old sony cd player or talking about upcoming exams within this setting was a hard reality to reconcile in my head. I won’t kid myself and pretend we were friends – I was just passing through their lives and them mine – yet I left knowing that had we grown up together, we very well could have been. I found in this wholly foreign setting something entirely familiar – young men talking about girls and music, posturing about who could run the fastest.

Although I am uncomfortable with it, I know why I am asked about “Africa” as if it’s one thing, as if I could offer an easy answer. In the States, our news so often treats the story of the complex and large continent as one of famine, disease, and oppression. Before my short travels in Tanzania, then president George W. Bush perpetuated an over-simplified and uninformed view when he summarized the continent as “a nation that suffers from incredible disease.” News from African countries is usually lumped into “African” news, and is usually bad whether or not it is representative of real changes, successes, and everyday life on the ground.

Upon returning home I wanted to avoid turning to stereotypes when talking about my trip. This goal became much harder when shortly after my return in early 2008 Kenya experienced serious post-election violence. For the average US citizen, Kenya may as well be Tanzania for all we know, and the story I was telling was overshadowed by the same old news out of Africa.

Stateside I was embarrassingly surprised to find myself receiving friend requests from some of the young Tanzanian men I had met during my travels. The exciting prospect of Facebook truly being a global phenomenon actually took form as my feed would occasionally be populated by KiSwahili posts and a grainy photos from Tanzanians using their cellphones.

My foray into just how global Facebook is was when a wildlife manager and tour guide I had met in Tanzania a shared gruesome cellphone picture of two cows of his which had been slaughtered by a lioness with four cubs. Our culture so often distances ourselves from our meat – I was shocked to see so much blood in my feed. What entailed was 30 comments commiserating but also discussing the most ethical reaction the man should take. As a country which relies on tourism, the safety of the wildlife there is paramount to the stability of Tanzania, yet many of the Maasai people and their livestock live in what has become protected national parks, causing many conflicting interests. New laws restrict protecting property from animals like lions and elephants while there is no insurance or compensation for the pastoral people most affected by them.

As a Maasai, the guide comes from a tradition of retributive killing of lions who attack their cattle, which is the Maasai’s most important commodity. Talking on Facebook about this culture, and a newer Tanzania which protects the wildlife, my tour guide was unsure of what he should do. Most encouraged him to leave the lion be, and try and get financial aid from the government who has often made hollow promises to the Maasai people who deal with this situation the most. One commenter reminds him of his duty as a wildlife manager, and the importance of a healthy environment for the future of Tanzania. Half a world away, this man was using Facebook to react, share, and debate the appropriate recourse for his friends both foreign and local to see. He thanks everyone for their condolences and support; he chose to not kill the lion.

With platforms like Facebook and Twitter, especially through Banjo, I can look back at Tanzania to recall what life looked and felt like there. I enjoy seeing what the people share, not the mediated news that shares on their behalf. I find that when I am feeling nostalgic for Tanzania, these citizen populated platforms feel much more accurate to my memory. My KiSwahili has slowly left me so I rarely speak back, but every so often I like to say hello.

Growing up in a small city in Indiana, I was always dreaming of an adventure. In high school I read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness with the passion of a naive boy looking for danger and mystery, and the book resonated with me. My decision in choosing a semester abroad in Tanzania was as uninformed as that – Tanzania felt like the farthest away from home as I could get both culturally and physically, it was an adventure. Being on the ground and living in homestays allowed me a window into the complexity. The news we get from Africa can’t end with Chinua Achebe or Joseph Kony, and it isn’t simply blood diamonds or Nelson Mandela; like visiting, the social web can help offer a more complex and a more nuanced view – one hopefully decided by the Africans themselves.

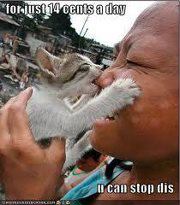

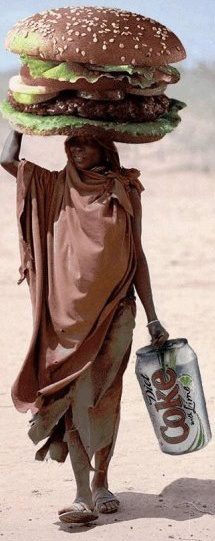

What is especially exciting to see is Tanzanians directly reacting to the western news narrative surrounding them online both in words and through memes. I hope to expand the casual research that began this article and begin collecting and engaging with a wider range of Africans who are involved in creating their own narratives online, whether toying with the image of the impoverished African or the typical starving African child commercial, pleading for 14 cents a day donations. I would love to hear from you, our readers, and ask for the fascinating memes, critics, and citizens you follow from the second largest continent.