Editor’s Note: You might remember Ben Valentine’s take on the “protest selfie”, a look at how the selfie has been used as a form of political expression around the world. We thought it would be great to look more closely at the selfie in context, and why 2013 really has become a year of the selfie.

Despite being around since 2002, selfie has taken the world by storm this year, causing Oxford Dictionaries to officially label selfie the word of the year. After only just adding it to their dictionaries in August of this year, Oxford Dictionaries wrote, “Language research conducted by Oxford Dictionaries editors reveals that the frequency of the word selfie in the English language has increased by 17,000% since this time last year.” A Photoshopped selfie of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair in front of burning oil-fields was even censored from billboards this year.

Interestingly enough, Oxford Dictionaries traces back the first ever recorded use of the word selfie, which is found in Australian online forum, ABC Online, on September 13, 2002, a whole three years before Facebook became an international force (unfortunately they don’t link to the source):

Um, drunk at a mates 21st, I tripped ofer [sic] and landed lip first (with front teeth coming a very close second) on a set of steps. I had a hole about 1cm long right through my bottom lip. And sorry about the focus, it was a selfie.

Having such mundane beginnings yet quite the meteoric rise, there is a ton of great readings investigating the selfie. I recently wrote about users using the #ProtestSelfie as a tool for activism and identification with causes, but I wanted to point you to some other great writings about the selfie I’d recommend to anyone.

I am personally excited and hopeful to see how selfies evolve. We as a society are accustomed to people being presented to us in public space thanks to advertising and mass media; needless to say, I don’t believe that sets a positive precedent for how we represent ourselves. Selfie are more representative of a user-driven description of who we are and how we want to create ourselves in the world. Of course humans like sex, and sexualized selfies abound and are often criticized.

However, we are also seeing selfies of people we hadn’t seen represented very often in mass media. People culturally understood as ugly, queers, people of color, and so on are all participating in selfie culture as a form of self-love and empowerment, and this is where selfies are most exciting to me. We see these marginalized groups carving out ever larger spaces for themselves online to be who they choose, flaunt it, love it, be proud of it, and share it. I think that’s beautiful, and I only hope to see those spaces grow bigger; I know selfies will be a part of that process.

Now, for the round-up of the best selfie writings:

The Selfie-Historical Context

Alicia Eler was a prolific selfie theorist this year at Hyperallergic, one of The Civic Beat’s favorite blogs (and for which our co-founder serves as a consulting editor). Having studied art history, I loved this post by Eler which understands the selfie inside of art history, which I think is really important whenever talking about an allegedly new phenomena. Eler writes in, “White Womens’ Bodies as Selfie-Objectified Tools of Dissent,”

I believe Mills’s posing with the Forever 21 bag covering her face speaks to her involvement in the ongoing objectification of white women on the internet, her own subtle attempt at expressing some sort of political dissent, opinion, or voice through the only means she can — her body. The body, after all, remains a battleground, maybe more so than ever in our current hypernetworked climate, where images speak more than a thousand words and travel even faster, and young girls who want to be seen just need to invest in an iProduct or two.

On Visibility and Self(ie) Love

On his Tumblr, Blaqueer writes:

I take my selfies because I am that guy who, unless he takes the picture or suggests it, doesn’t get his picture taken. My friend who asked, truthfully had very little right to judge; everyone takes pictures of him, with him, and for him. The same is true of almost all my friends. I live in a world where I didn’t hear someone romantically call me beautiful and desirable till I was 26. I live in a world where either body privilege or race privilege is always against me. So I point my camera at my face, most often when I am alone, and possibly bored, and I click; I upload it to instagram, and I hold my breath because the world is cruel and I am what some would call ugly, but I don’t see it. At first I clicked so I could see what others saw, but I don’t. So now I click and post and breathe, waiting for others to see what I see: beautiful dark skin, Afrika’s son, a dream un-deferred, pretty eyes,and nice lips, and a nose that fits my face; I want them, you, to see that I am human, and there is a reason why I got to this size, but I owe you no explanation or justification for any part of my existence I owe you no explanation or justification for my smile or my swag or my selfie. Hell I didn’t even owe you this.

“Our Selfies Our Choice: Why “Feminist” Writers Need To Stop Judging Our Instagrams,” Malia Schilling recounts how her understanding of the selfie has changed through the #FeministSelfie hashtag on Twitter:

Selfies can be self care and self love without “male gaze” approval. Selfies can be visibility for underrepresented minorities. Selfies can be personal affirmations that you are here and you’re not going anywhere. And in my opinion, an equally valid #feministselife can be unashamed, pure, beautiful and unadulterated vanity because you look amazing today and you love what your hair is doing right now and everyone needs to know it. The need for validation and support doesn’t stem from a selfie culture, it is an integral part of our relationships with each other. It’s not wrong to want to be validated, it’s human.

“My Selfie, Myself” by Jenna Wortham:

And selfies strongly suggest that the world we observe through social media is more interesting when people insert themselves into it — a fact that many social media sites like Vine, a video-sharing tool owned by Twitter, have noticed.

The Page One Selfie

Image via Matt Pearce, @Mattdpearce.

“A Page One Selfie” by Nathan Jurgenson, on the New York Times using a selfie of the Boston Bomber on their front page (above):

Granting, of course, that Dzhokhar’s face work was certainly of a radically larger scale, selfie face work is a sort of fiction that is a common fact. The filtered selfie isn’t the most objectively accurate photo, but it might have been the most honest. It’s how he presented himself, down to the name-brand shirt, and it’s how many people his age understand and perform for increasingly ubiquitous photographic documentation. It’s a sort-of unreality that’s carries a sort-of truth. The selfie isn’t just any photo of you, it is, of course, one taken of yourself, by yourself, and there is something simultaneously fitting and upsetting in the young bomber taking his own mugshot.

The Page One bomber selfie also challenges what many of us thought the bomber would look like on the day the tragedy occurred. This image doesn’t conform to what “we”, as a culture, wanted, perhaps even needed, the bomber to look like. Instead of the stereotypical guy-in-a-cave or guy-in-a-shack, Dzhokhar here looks like someone we might know. More than that, given that this is an Instagrammed selfie, he even acts like someone we know, someone we recognize as “normal”. It breaks from the script: The bomber was never supposed to be so familiar.

Beauty and the Selfie

“Ugly is the New Pretty: How Unattractive Selfies Took Over the Internet” by Rachel Hills:

For Ford, the ugly selfie serves as a cheeky offset to her own vanity. “Whenever I upload a photo that is deliberately constructed to make me look appealing in some way, my rule is that I have to also upload one taken of me looking monstrous or ridiculous,” she explains. “It puts personality back into a superficial practice of self-documentation that has become devoid of anything real.”

“The Power of Instagram: Petra Collins and Kim Kardashian in the Age of the Selfie” by Katherine Bernard

It’s as if we think, if one side is loud enough, some omnipotent Internet deity will announce a winner: “Attention humans: She is, in fact, fat. ‘Yeah’ commenters win.” But the truth is, our reactions to young women with sexual confidence reveal more about us than it does about them. Our selfie culture is a mirror of our values. Or Collins puts it more darkly: “ . . . these very real pressures we face every day can turn into literal censorship.”

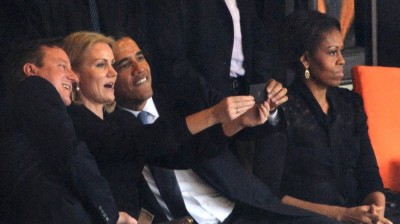

The Obama Funeral Selfie

And, naturally, the infamous “funeral selfie” taken by President Obama, Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt and British Prime Minister David Cameron during the memorial service (not technically a funeral) of Nelson Mandela. Mashable’s Chris Taylor had this to say:

The point is, we don’t know the full context of what would be, for almost any other three people in the world, a private moment. Without that knowledge, a rush to judgment dishonors the memory of a man who spent decades fighting a society that systematically rushed to judgment.

Image may be king in politics, but it’s high time that king was dethroned.

And So It Goes…

Despite much critical praise and growing usage, selfie, and its identification as word of the year was met with a harsh backlash, which Joy of Tech nicely captures (above). Really though, language is always changing, so while I am sure the craze around moralizing the selfie will die down, selfies are here to stay. I for one am very excited to see more people confidently representing themselves in the media I consume.